When Quentin Tarantino Met Franco Harris at George Romero's "Land of the Dead"...

In considering a story for Super Bowl weekend, I did for a moment think about Patty, the woman I met making My Tale of Two Cities in Blawnox who owned an intimate apparel shop and turned “The Terrible Towel” into lingerie. Patty told me that when the Steelers won, she would see a significant boost to her business which is telling about Pittsburghers and their libidos. Frankly, growing up in a sports-dominated town as an awkward, uncoordinated adolescence I had a complicated relationship to football. But a good deal of my childhood resentment towards the sport was healed when I had the privilege of spending some time with Steeler great Franco Harris.

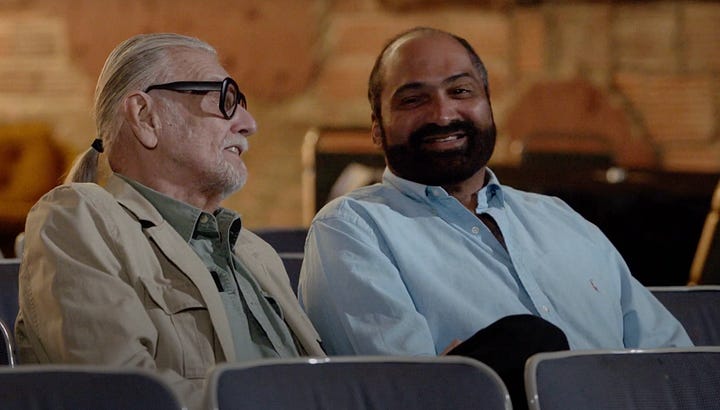

The first time I met Franco was when he tapped me on the shoulder at the premiere of George A. Romero’s Land of the Dead and asked if I could introduce his son Dok to Quentin Tarantino. Quentin was in town for the premiere/fundraiser I was co-hosting with Steeltown Entertainment co-founder Ellen Weiss Kander— an event that the Post-Gazette called the “greatest non-sports love-fest this town has ever seen.” I was surprised when Quentin could recite all of Franco’s stats on the gridiron, but if I recall correctly, I believe Dok later told me he suspected his father had not seen any of Quentin’s films. For many, Hall of Fame running back Franco Harris is most remembered for catching a pass in 1972 which bounced off an Oakland Raiders’ helmet just before it hit the ground and running it into the end zone to win the game. That improbable touchdown catch has been voted number one of the NFL’s top 100 plays and is known as “The Immaculate Reception.” To give a sense of the reverence for number 32 in this region, in the airport, you are greeted by two statues—one of a young George Washington who fought here in the French and Indian War, and the other of Franco Harris catching a football with the caption: “Two great battles fought in Western Pennsylvania.”

There are others better qualified to talk about why Franco was such a great player on the field, but in keeping with my pledge to share one “sacred stories from these three rivers” every week, I wanted to talk about how, in my experience, the Franco was an even a more inspiring person off the field. After that “cute meet” at the Land of the Dead premiere, Franco and Dok agreed to appear in the documentary we were making My Tale of Two Cities, about the city which built America with its steel, conquered polio and invented everything from aluminum to the Big Mac, but was struggling to reinvent itself in a post-industrial age. At that time, in 2005, many had written off Pittsburgh with Money Magazine proclaiming it the “Not Hot” place to live. To make matters worse, even the town’s beloved Steelers were losing. For our film, we talked to various Pittsburgh’s neighbors asking them if they believed Pittsburgh could once again become “The City of Champions.” We spoke to Joanne Rogers as she played the Steinway piano in the studio where her husband Fred had taped his show for forty years; philanthropist Teresa Heinz Kerry with whom we went shopping in The Strip District where she used to shop her first husband, the late Senator John Heinz; and ate breakfast at Ritter’s diner with former Treasury Secretary Paul O’ Neill where he had gone each morning at 5 a.m. when he was the CEO of Alcoa. When we asked Franco if we could film at Heinz Field, he instead asked if we could meet him on the North Side in the Mexican War Streets where he still owned the modest house he bought when he began playing for The Steelers. It was from there that he and team owner Art Rooney, who had won the football franchise in a card game, used to walk to the games together.

During our walk around the neighborhood, I confessed to Franco that I had not been a Steeler fan in the 1970s, but rooted for the Minnesota Vikings. Franco smiled and said that was okay, though added it was not the smartest choice. The truth was I hated football because I was a scrawny, picked-on kid, and I liked the Vikings because their quarterback, Scramblin’ Fran Tarkenton, ran away from the big guys, which I fantasized about being able to do and my childhood friend Michael Alteri had convinced me they were cool. (And I liked the color purple.) Instead, whenever the Vikings lost to the Steelers, I was shoved into lockers, most famously in the Super Bowl IX in 1975 where Franco was the MVP. I was surprised to learn that Franco had sent his son Dok to.a high school which had no football team. When I asked why, Franco explained he had taken Dok to a playground to play basketball when he was five and kept passing him the ball, and told him to keep going, keep going. After a few minutes, Dok said “I’m tired” and Franco accepted his son was never going to be a ball player. For the record, Dok disputed this story as he had just beat his Dad in a game of one-on-one. But rarely whatever his athletic prowess, I had never seen a man who so obviously loved his son as much as Franco loved Dok whose actual name is Franco Harris Jr.— Dok being from Franco’s wife Dana Dokmanovich’s maiden name.

In talking about what might save Pittsburgh, I asked Franco straight out whether it would be people like his brilliant son who had gone to Princeton and come back to go to business school and law school at the same time, or some guy catching a touchdown pass? The question seems a bit rude of me now looking back, but Franco asked why I had to separate things, why did it have to be one or the other? He said he loved how this city, his adopted hometown as he grew up in New Jersey, had a great symphony, ballet, and arts community. He said a city need many things— sports, the arts, medicine, great schools— to make it complete. I had stereotyped Franco as just another football player, but found him time and again to be so much more than that.

I could list for you many of Franco’s civic achievements and the way he gave back to the city— how he chaired The Pittsburgh Promise so that any kid who graduated from a Pittsburgh Public School would have the chance to go to college; the good deeds he did as someone who sat on the board of the Heinz Endowments; or privately the good works he personally funded for those in need. But what stays with me most is an encounter he had with two young kids we met before we started filming. They both shouted out “Franco!, Franco!” and I was amazed these not yet teenagers even knew the man who wore the Black and Gold number 32 decades before they were born.

“Are you still rich?” one asked as he stood in front of his modest house on the Mexican War Streets. He replied “what does rich mean?” assuring them money can’t buy you a lot of things. Then he told them the most important thing was “to be happy with what you make.” They pointed to a fancy car on the street and asked if that was Franco’s. He said actually he drove that beat up old one, indicating an old Jeep. “It get me where I need to go.” Then he asked these two kids staring at him expectantly what they wanted to be when they grew up. They both quick spurted out: “Football players.” Franco laughed and said that was too easy. He then asked what they really planned to be. One said a lawyer, the other said a fireman. He said okay then, and shook their hands as he said he looked forward to meeting them again one day when they were a ball player and a lawyer and a ball player and a fireman.

I showed that clip at the Beverly Hills home of a talent manager who had become the first to get $20 million for a film for his client Jim Carrey. The manager shook his head, and lamented how few people he knew could say they were happy with what they make— no matter how much that was. Today more than ever, when it seems even billionaires are not satisfied until they have trillions, Franco reinforces there are some who do things for more than just making money. In this day an age where so much seems to be about Benjamins, Franco to me was a man who never seemed to sell out.

Even his businesses sought to do good and do well. He founded “Super Bakery,” a company realizing there were poor kids who go to school without getting breakfast and giving them a donut with nutritional vitamins might help. As opposed to the fierce competitor he was known for being on the field, the Franco I knew was such a gentle giant. He showed up at a screening of a movie I was making about the Salk polio vaccine and shared how he still remembered getting “the shot.” Though the guy broke rushing records with his speed, I remember once his wife Dana lamenting about how long it took Franco to pick out blueberries in a supermarket.

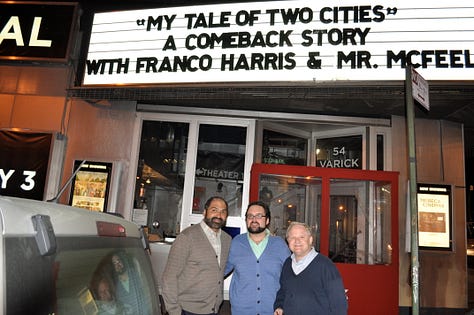

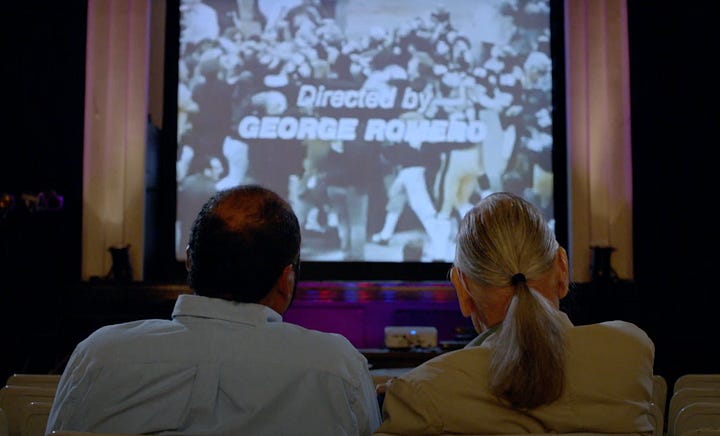

I have many other fond memories of Franco which still make me smile. He had volunteered to go to screenings we had of My Tale of Two Cities in New York at the Tribeca Theaters and in D.C. where we were the first film to play at the Capital Hill Visitor Center. He knew his presence would draw a crowd and we sold out every screening. Afterwards, Franco would talk, often with David Newell “Mr. McFeely,” about why he thought Pittsburgh was still a great city and why he felt people were writing it off just as they had written off the Steelers before he came to Pittsburgh. Before Franco joined the squad in 1972, the club was known for being the worst team in football, finishing one season 1-13. His rookie year, Franco helped lead the Steelers to their first playoff game in 25 years and they would win four Super Bowl titles in the decade that followed. Ironically, this was just as Pittsburgh was losing the Steel industry and its job. Those terrible towels you see waving at games around the country are often being held by Pittsburghers who were forced to leave their dying hometown to go elsewhere in search of employment. This is all brilliantly told in the NFL special Night Of the Living Steelers starring George Romero and Franco Harris. Between his zombie movies, George Romero actually made two documentaries in the 1970s about Franco in his days with long sideburns and at the height of Franco’s Italian Army. It is only now looking back that I realize how Franco helped bridge racial divides in what is too often a highly segregated Pittsburgh.

I discovered the affection that so many still felt for their hometown the night we premiered My Tale of Two Cities at the same Byham Theater where the Land of the Dead had premiered. It was to screen on the Friday of Thanksgiving weekend when many returned home to visit relatives still in the Burgh, and I was shocked to get a phone call from the theater on Monday telling me we had already sold out all 1400 seats. We had similar successes wherever we screened the film out of town, frequently fueled by expatriates in towns which had thriving Steeler bars where like church, each Sunday fans of the faithful would congregate. After one of our My Tale of Two Cities screenings out of town, Franco and I were at the airport and he offered to give me a ride home— even though I was in the East End and Franco lived the opposite the direction. As we went through the tunnels, I started given Franco directions about which exit to take, and he said “Are you trying to tell me how to get to Oakland?” Franco was funny in a way that often caught me off guard. He would never fail to stop and be gracious to every fan who came up to him, many who had stories about where they were during The Immaculate Reception. But when I suggested that maybe he should get a website, he asked “Do you really think I need to be more visible?”

Having made documentaries since I had come to Pittsburgh about the Salk polio vaccine, transplant pioneer Dr. Thomas Starzl, and even George Romero, I went to a theater where they were playing the old documentaries Romero had made on Franco. and asked Franco if I could make a documentary about him. He was modest when I brought it up, feeling like he had had enough time in the limelight. When the NFL did a documentary on Franco Harris: A Football Life, they began with him in front of The Crawford Grill, a once iconic jazz club in Pittsburgh’s Hill District which he was determined to restore back to its former glory. It was the club where everyone from Duke Ellington to John Coltrane played, and was mentioned in several August Wilson plays. I have been producing a documentary on August Wilson’s formative years in Pittsburgh and the struggles of The Hill District where he set many of his plays to reinvent itself. When I asked Franco if he would be in it talking about The Crawford Grill, he immediately said yes.

We had that conversation on Walnut Street, just a couple of blocks from Pembroke Place where I had grown up playing street football with my brother, my friend Michael Alteri (who had gotten me into The Vikings) and occasionally Stevie Soderbergh who would gone on to be a huge director in Hollywood (Sex, Lies & Videotape, Ocean’s 11) Franco was with Dok and Dana, and I was with my brother Tom, and for some reason, Franco chose that time to ask my brother what kind of a ball player I was as a kid. Both Franco and my brother had a good time ribbing me about my inability to play football. In My Tale of Two Cities, my old gym teacher Bob Grandizio pointed out that if I had any ability to catch a ball instead of letting me hit me in the face, I might have had a shot of having a girlfriend in high school. Instead, he pointed out I had to go to Hollywood where girls like artsy, un-athletic guys like me where I eventually met my wife Natalie.

It is obvious that when I came back to Pittsburgh, I had some old wounds from my childhood. But one of the moments which has been the most healing was getting a chance to toss a football around with Franco and Dok on the North Side of Pittsburgh during the making of My Tale of Two Cities. As we were playing, a vehicle came by and Franco called “car” just like we used to call playing street football on Pembroke. After the shoot, Franco signed the football for me. He wrote “Believe in Pittsburgh.”

I never got the chance to film Franco for that August Wilson documentary, as he died a few days later, just shy of the 50th anniversary of The Immaculate Reception. The Steelers are not in the Super Bowl this year, but when I watch the game, I’ll be thinking about Franco. In these days where it is sometimes hard to believe in anything, it is reassuring to know that every time I go to the airport, I see the man who I and so many others who met him still look up to. Oh, and I guess that George Washington was a pretty good guy too.

Franco Harris encounters two young fans and gives them sage life advice

The “sizzle reel” we made to raise money for the movie which included a scene with Patty at her intimate apparel shop where she turned The Terrible Towel into Lingerie.

The trailer for “Night of the Living Steelers.”