Hollywood's Best Kept Secret and The Power of Pittsburgh Mothers

starring the mothers of August Wilson, Gene Kelly, Andy Warhol, Steven Soderbergh, and many more

In 2003, as part of the Steeltown Entertainment Summit held at the Fred Rogers Studio, I produced a short film “Pittsburgh: Hollywood’s Best Kept Secret” featuring Oscar-winning actress Shirley Jones, director Rob Marshall (Into The Woods, The Little Mermaid), Animal House co-star and TV director Jamie Widdoes, talent manager Eric Gold, producer/executive Bernie Goldmann (300), and others talking about how Pittsburgh had nurtured them and its potential for becoming a player in the entertainment industry. This all began when my friend Bernie Goldmann, who I knew from my days in LA, came to speak to my students at Pitt about how he had gone from hanging out at Taylor Allderdice eating Mineo’s Pizza to becoming the President of Village Roadshow, the company that produced The Matrix, Training Day, and Ocean’s 11. (Bernie and I used to FedEx Mineo’s when we were homesick.) Bernie’s mother Rita showed up, and then a woman Roz Markovitz asked why I didn’t invite Eric Gold to speak. She explained that he and his partner Jimmy Miller, also from Pittsburgh, co-founded Mosaic Media that represented talent like Ellen DeGeneres, Vince Vaughn, and Will Farrell. I explained we didn’t have a speaker’s budget to bring him in and she said that was okay because Eric came to town all the time to visit his mother Thelma. The same would be true for actor/director Jamie Widdoes and his mother Babs, and sitcom writers Maxine and Sally Lapiduss and their mother Esther who was a prominent entertainer in Pittsburgh’s theater scene where my own mother also had worked as an actress, and then I got a call from Terri Minsky’s mother Joan asking why I hadn’t spoken to her daughter who had created Lizzie McGuire based on her experiences growing up on Mt. Lebanon. This was the year Rob Marshall was nominated for an Oscar for directing Chicago and told the Post-Gazette he wanted to thank Pittsburgh where he grew up on “a buffet of the arts” with a world-class symphony, theater community, museums, and The Civic Light Opera where he and his sister Kathleen, a Tony-winning theater director, got their start.

Why is it that so many who have grown up here have gone on to have such great success on Broadway and in Hollywood? The answer may lay in something Rob Marshall once told me about artists being formed between the ages of 8 and 14. But it is also because of the mothers who raised these kids by these three rivers.

This Saturday I am going to see Radio Golf at the August Wilson House, the last play of August Wilson’s American Century Cycle— which includes the Pulitzer Prize-winning Fences and The Piano Lesson— nine of which are set in The Hill District where August Wilson grew up. Denzel Washington, Oprah Winfrey, Samuel Jackson, Shonda Rhymes, Tyler Perry, and Antoine Fuqua donated $5 million dollars to transform the childhood home into a community arts center. The family didn’t own 1747 Bedford, but his mother Daisy raised August with his five brothers and sisters in two modest rooms in the back. She saw great potential in her bright son who loved to read and wanted him to be a lawyer. But Freddy Kittel, as he was known then, dropped out of 9th grade after a teacher accused him of plagiarism on a paper he wrote about Napoleon. Freddy didn’t tell his mother and instead went every day to the Carnegie Library where he read every book he could get his hands on At twenty, Freddy decided to be a writer and adopted the pen name August Wilson using his middle name and his mother’s maiden. The man who today is regarded as “America’s Shakespeare” wrote ten plays about Black American life, each set in a different decade of the 20th Century, inspired by the stories he first heard from his mother.

The whole notion that this city has been an incubator of all this talent began after I read an article citing a poll that said that a significant number of Pittsburghers were against a statue in downtown being proposed for Gene Kelly, saying he should not get such an honor because he left Pittsburgh. I wrote an email to my mother’s old friend Chris Rawson, a theater critic for the Post-Gazette, saying how I had met Gene Kelly out in Hollywood when I had gone on a date with his daughter Bridget, and just by that brief encounter, I could tell how Pittsburgh had shaped the greatest star of musical movies the world has ever known. Chris would publish that email as an article with a headline “Gene Kelly took Pittsburgh with him to Hollywood.” It pointied out Kelly’s relentless work ethic (Debbie Reynolds talked about what a taskmaster he was as they made Singing In the Rain), his athleticism (he did a TV special Dancing: A Man’s Game with Yankee Mickey Mantle and boxer Sugar Ray Robinson), and his everyman perspective— just look at the “Gotta Dance” sequence in Singing In the Rain where he plays a rube coming to the big city. Gene Kelly had grown up in East Liberty where he dreamed about being a short stop for The Pirates, but his mother Harriet made him take dance lessons. He would be teased by the neighborhood boys, but he was such a great dancer that Harriet would later make him go into business with her opening The Gene Kelly Dance Schools. I later heard from many mothers in Squirrel Hill who had gotten dance lessons from Gene at Temple Beth Shalom before he left Pittsburgh for Broadway and then Hollywood.

Last week the Pittsburgh Vintage Grand Prix was held where classic cars race on Serpentine Drive in Schenley Park benefiting The Allegheny Valley School— an event I first heard about from Mary Ann “Midge” Soderbergh. Little did I realize that Stevie Soderbergh who I once played street football with in middle school would grow up to be Steven Soderbergh who directed films like Ocean’s 11, Erin Brockovich and Magic Mike (with Pittsburgh’s own Joe Maganiello whose mother I would also meet.) The truth is I more remembered Steven’s sisters Cathy and Mary Ann, the latter who pinned me to the ground and threatened to burn me with a cigarette until I swore—a scene I would reenact in My Tale of Two Cities. My thing about swearing came from when I would have to run lines with my mother who was starring in plays at The White Barn theater when I was a kid. She would make me run lines with her that sometimes involved curse words like “Jane you G-ddamn whore” and I would make up words like “Dungledorp” just to avoid cursing at my mother. She would swear every fu*#&ing third word, so out of rebellion, I refused to curse. That’s why Mary Ann Soderbergh held a lit cigarette inches from my face at the Liberty School playground and would not move it away until I said “F-U-C-K.”

Pittsburgh was not an easy town to grow up in during the 1970s when everyone just cared about the sports teams, especially if like me, you were totally uncoordinated. I used to sit in front of the TV set on the floor in my mother’s room with a bowl of Cap’n Crunch or Quisp cereal, doing my homework in front of F Troop where I had a crush on Wrangler Jane, Gilligan’s Island where I was a Mary Ann fan (Ginger reminded me too much of my mother) and Petticoat Junction where I would watch the opening credits with Billie Joe, Betty Joe, and Bobbi Joe bathing in that water tower and pray just once the camera would slip and reveal the sisters in all their glory. I was, in short, a lonely nerd with zero social life, but my younger brother Tommy was more athletic and loved football so when the kids on the street were desperate for someone to even the sides, he and our friend Michael Alteri would throw a football at my mother’s bedroom window and beg for me to come out.

Michael was slightly older and we all knew would end up in the NFL as he could catch anything. When we played two-on-two, I would end up on Michael’s side and he just have me chuck the ball as far as I could and yell “WHIPPP—ITT!!!!” Somehow wherever it went, Michael would snag it out of the air. Once I accidentally heaved the ball out of bounds at a “No Parking” sign and Michael collided with it head on, was momentarily knocked unconscious, but still caught the ball. Michael and Tommy preferred when Stevie Soderbergh from Kentucky Avenue could play as he was good, but his mother sometimes would not let him. It would turn out that Steven’s father Peter was teaching film at Pitt at the time, but when he didn’t get a full-time position, the Soderberghs moved to Louisiana where Peter became a beloved Dean at LSU and where Steven pivoted from sports to a new passion he discovered— the movies.

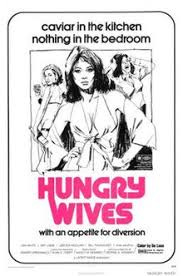

Being from Pittsburgh, I had no idea one could make a living in the film business, and the only exposure I had was when my mother was once in a George Romero movie. That was its own traumatic experience as she had me come to dailies with her where suddenly the lead actress playing a witch in some sort of coven robe was disrobing and mother sent me out to get her a pack of cigarettes. I had never seen the movie as it was titled Hungry Wives and I was always worried my mother was naked in it. Recently, it was restored and retitled Season of the Witch and the film actually makes a powerful statement about feminism. (And it turns out my mother kept her clothes on.)

My mother and brother Tom who would become an actor in Hollywood (Kindergarten Cop, Young Guns II) were the creative ones, and my mother expected me to be a doctor. That was partly because I was the studious type and partly because she had married a couple of gastroenterologists. That led to my writing my first joke: “My mother has this habit of marrying doctors—my real father Donald is a doctor from Cleveland, my step-father Richard is a doctor from Pittsburgh. My mother never get divorced—she just gets referred to another husband.” Ba dump bump.

We had come to Pittsburgh when I was eight because my mother had married Richard, who had three kids on his own, and my brother Tom and I lived in his castle-like house in Squirrel Hill which came complete with a turret like the real life Brady Bunch. But that union would last only eighteen months and after the divorce, my mother moved us into a two-bedroom townhouse in the then funky section of Shadyside. We lived above a preppy men’s clothing store Kountz & Ryder and every time our bathtub would overflow, the owner Frank would bang on his ceiling with a broom and yell how his alligator shirts were getting wet. My mother insisted on keeping the TV in her room because she would watch the commercials, as she supported us as best she could with her acting, doing commercials and voiceovers. She had been a promising actress when I was born in Chicago studying with Viola Spolin, the “mother” of Second City, and starring in “The Hamlet of Stepney Green” with comedian David Steinberg. It was the Jewish version of Hamlet, and I envisioned it going something like: “To Be or… can I get a corned beef on rye?”

It was not easy to make a living as an actress here and Pittsburgh was not a happy place for my mother. She spent much of my adolescence on her bed playing four- handed bridge by herself, smoking Salem’s, waiting for my ex-step-father Richard to call. (Even their divorce was unsuccessful as they would have on-again/off-again affair for years.) Sometimes, around midnight, my mother would look up from her red deck and share words of wisdom with me like “Son, in life, there are the vaudevillians and the mundanes. And because your father was a doctor who went to the same office every day, he thought he was a mundane. And because I was an actress on the stage at night, he thought I was this great vaudevillian. But the truth is inside every vaudevillian is a mundane and inside every mundane is a vaudevillian.” And then she would go back to shuffling her cards. When I got out to L.A., I told that story to Dick Clark, who had his own production company as well as American Bandstand,. He thought my mother sounded like quite the character and did an option deal for a TV show with the working title: “Carl’s Mom.”

One day my brother Tom and I came home to find a yellow moving van in front of our apartment and our mother informed us she was running away from home to pursuit her long postponed dream of becoming an actress on Broadway. She couldn’t afford to take us with her so she arranged for us to get scholarships to Shady Side Academy, which only had five-day-a-week boarding. I ended up babysitting on the weekends for the Nassif family who owned the St. Elmo Hotel in Chautauqua, New York. They offered me a summer job there which led to me meeting a waitress Lynn who I became infatuated with who inspired my first short story “St. Elmo’s Fire” and then the movie St. Elmo’s Fire that launched “The Brat Pack.” Lynn Snyderman would become Dale Biberman in the movie and would be played by Andie MacDowell, with Emilio Estevez playing my nerdy alter-ego Kirby Kager (the name was a variation of a friend I was in carpool with in middle school.)

Turns out Andie MacDowell had a colorful mother which I heard about one night when we went to dinner and started exchanging mother war stories like the scene on the boat in Jaws where Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw show each other their scars. Before becoming a famous supermodel, winning America’s heart in a Calvin Klein ad where she talked about her two friends Dot and Earl who lived in a trailer but had a dream that some day, some day, they would see Atlanta, Andie had a challenging childhood in Gaffney, South Carolina where she and her three sisters were raised by a single mother Paula who battled alcoholism. Andie actually trumped me when she told me about how when she was in high school, she and her mother were both working together at a McDonald’s, and as if that wasn’t embarrassing enough, her mother got fired for drinking on the job.

A couple of years later, I saw an early cut of Sex, Lies, and Videotape and was blown away by Andie in the movie. I called to tell her how great she had been, and asked her about her performance. She gave some of the credit to her director Steven who she mentioned kind of reminded her of me. I don’t recall if I realized then it was the same Stevie Soderbergh I had played street football with. I did notice when in one of his next movies King of the Hill, a coming-of-age story about a 12 year-old based on the memoir of A.E. Hotchner, the kid’s last name was Kurlander. Maybe a coincidence or maybe Rob Marshall was right about artists being formed by what happens to them between 8 and 14.

I never got to meet Steven Soderbergh as an adult, but I did get a call from his mother Mary Ann “Midge” Soderbergh, who like my own mother, was a character, or to use my mother’s parlance— a Vaudevillian. We had lunch several times and she told me how she had been a Marine in the Korean war and done photography and filmmaking and was writing her own stories. She was fascinated by the supernatural, and like my mother, felt a connection to the spiritual world. She also talked about her eldest son, Peter, who was autistic, and living at The Allegheny Valley School which provides services to those with disabilities. Such things were less understood or discussed back in the 1970s and I wondered if that was why she was cautious about her younger son Stevie playing football with us. Midge and her husband got divorced a few years after they left Pittsburgh, and I heard in an interview Steven talked about how he was closer with his father, but he conceded that his mother had also shaped him as an artist. Soderbergh even used her maiden name as a pseudonym when he edited his Liberace movie Behind the Candelabra and Mary Ann Bernard lived to see herself win an Emmy.

The Mothers Lunch

The Gene Kelly article I wrote had led to an op-ed “Pittsburgh’s Next Industrial Revolution: Entertainment” in which maintained just like Pittsburgh had natural resources like iron and coal to make steel, it had so many resources with his cultural assets and universities, but now Pittsburgh’s greatest export was no longer steel, but talent. That talent had made billions for studios in Hollywood, and with Western Pennsylvania facing great economic devastation since the collapse of the mills, I suggested perhaps it should try to enlist some of those entertainment expats to help with the city’s revival and reinvention in the digital age It took several other mothers to run with this vision and put it into action.

When my wife Natalie and I bought a house here in Pittsburgh, a spirited twenty-year-old Nina Fisher came to sublet our old place. Her mother Audrey Hillman Fisher came to check it out, and when she read my article, being civic-minded, Audrey suggested we create the non-profit Steeltown Entertainment Project. I tried to point out that the entertainment business was a for-profit, and she said she was on the board of a non-profit that made a profit called UPMC and she believed “The Arts” (if redefined as the creative industries) could become a great economic engine for the region like medicine had since the collapse of the steel industry.

This was right around the time I ended up on Oprah for of all things moving to Pittsburgh. It turns out when I went to L.A. in the 1980s when those steel mills were closing, so did a lot of other folks and suddenly I started to hear from more mothers telling me how their kids who had also done well in film and TV. Lucy Fisher, the director of Pitt’s Film Studies program, suggested we have a “mothers’ lunch” at The Pitt Club. In attendance were Natalie Beckerman whose son Jon was the head writer of Late Night with David Letterman; Louisa Rosenthal whose son Mark was the COO of MTV; Barbara Ackerman whose son Peter co-wrote Ice Age; Rita Seltman, Bernie’s mother. As President of Villlage Roadshow, Bernie had been on the set of Training Day talking to Ethan Hawke who was bragging about who went to his high school, when Bernie mentioned how both Rob Marshall and Antoine Fuqua, the director of the film they were working on, had gone to his high school Allderdice. (I have never met Antoine or his mother, but he has not forgotten his Pittsburgh roots, as he was born in The Hill District and was one of the major donors to the August Wilson House.)

Babs Widdoes was the luckiest mother of all, as she made her entrance with her son Jamie on her arm. He was still recognizable as “Hoover”, the fraternity President in Animal House, ad had become on of the most successful directors in television (8 Simple Rules, Two and a Half Men, Mom.) Jamie would attribute his start in show biz to helping his mother squeegee the stage between storms when she became the first director of the Three Rivers Arts Festival. He also knew Audrey as Babs was close with her mother Elsie Hillman, one of the city’s leading philanthropists, and so he also thought this idea of starting a non-profit Steeltown Entertainment Project to help Pittsburgh was a great idea.

Though she could not make the mother’s lunch, Eric Gold’s mother Thelma became a trusted Steeltown adviser also (dragging Eric along on the way.) When he first came to talk to my students, Eric had Vince Vaughn on the phone and asked if the classroom where he would be giving his talk had some sort of amplifier so Vinny could say “hi” to the kids. But when we went into the packed auditorium, Eric pulled me aside and explained he could not speak until I moved the lady in the front row to the back of the room. That lady would turn out to be his mother Thelma, and though I moved her, she heckled him throughout, insisting on her version of events of how he had gone from working with her at Pittsburgh’s Holiday House in Monroeville to become one of Hollywood’s most successful managers. Thelma’s banter was as funny as any of Eric’s clients, and later, he confessed he never closed a deal without talking to Thelma, including when he got Jim Carrey his first $20 million paycheck.

It would take one more mother to make the formation of the Steeltown Entertainment Project a reality. A few months after Eric spoke on the Pitt campus, I got a call from Maxine Lapiduss whose mother Esther had been a legendary local performer at the time my mother was doing theater in Pittsburgh. Maxine introduced me to her childhood friend Ellen Weiss Kander who had gone to school with her and Robbie Marshall. Ellen had a son Jacob who was creative, and, hearing about Steeltown’s mission, Ellen, one of the kindest most giving people I have ever met, volunteered to be Steeltown’s first executive director. She truly believed “entertainment could become Pittsburgh’s next steel” and frankly everyone loved her and so wanted to do things for her to make this vision a reality. Ellen introduced me to her good friend, the dynamic Anne Lewis who at the time was chair of The Children’s Museum and somehow agreed to be the board chair of our humble start-up non-profit, and we were off and running.

In October 2003, we hosted the Steeltown Entertainment Summit which PG writer Ron Weiskind called “the greatest assemblage of talent and hustle this town has ever seen.” We had such a modest budget that we could not afford to fly anyone in or put them up so some of these titans of show biz ended up staying with their mothers. (Or perhaps more likely, their mothers insisted.) We filmed the three hour summit at the Fred Rogers Studio with everyone sharing their ideas of how this old Steel City could become a regional entertainment capitol and programs that might provide opportunities for emerging talent here. That was cut to an hour TV special including the premiere of Pittsburgh: Hollywood’s Best Kept Secret and that show was nominated for a Mid-Atlantic Emmy.. There was also a party at Andy Warhol Museum where Lenora Nemetz, who had starred in Chicago on Broadway, sang “All that Jazz” for Rob Marshall while Handy Man Joe Negri from Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood accompanied her on his smoking electric guitar.

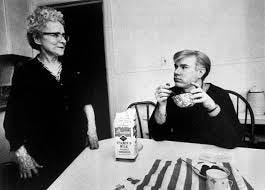

When Andy Warhola was growing up in Oakland, his mother Julia who was artistic herself, had her sickly and pale child help her paint elaborate Carpathian eggs. Seeing his talent, she enrolled him in art lessons at the Carnegie Art Museum. Andy would study art at Carnegie Tech, but the day he graduated, he took the first train out of the city. However, Warhol Museum director Tom Sokolowski pointed out Andy chose to paint subject matter of Pittsburgh’s working class like Brillo boxes and Campbell Soup and called his art studio, “The Factory” as a nod growing up in a mill town. Andy was often elusive about his past, but he always gave his mother full credit for inspiring his art and even collaborated with her on a few pieces.

When he left Pittsburgh in the 1950s, he took Julia with him and she lived with him in his New York apartment until shortly before she died. While making My Tale of Two Cities, I asked Andy ’s nephew Marty Warhola who runs a scrap yard next to the Warhol Museum what would have happened if Andy had stayed in this city. Marty smiled and said he probably would’ve worked in his uncle’s produce business. But then again, he was a genius…

During the Steeltown Summit, we talked about the big question which had come up at the mother’s lunch: What was it about Pittsburgh which had created a disproportionate number of successful people in film, television, and on Broadway? The mothers came up with five things that they felt were part of the equation:

1) A relentless work ethic. Despite the public image, the entertainment industry is not for the squeamish with a huge failure rate and a minimum 12 hours workday on set. But it is easier than working in a steel mill and while others came to New York to be seen at Sardi’s or to L.A. to indulge in sun and fun, Pittsburghers kept their head down and did the work.

2) An every man’s perspective. Whether you a Gene Kelly or Michael Keaton you don’t need to do market research or wonder what audiences will think when you are coming from this quintessential American tawn. My favorite Pittsburgh joke is in Sullivan’s Travels where the director defensively tells a studio boss that his last picture did okay in Pittsburgh, to which the boss retorts: “if they knew what they like, they wouldn’t live in Pittsburgh.” But in reality, Pittsburgh is the heart of America and perhaps that is why the country embraced Fred Rogers as their neighbor, and even George Romero and the zombies he invented here.

3) An exposure to the arts. Pittsburgh’s great industrialized patronized the arts, seeding the city’s great symphony, numerous museums, and a thriving theater community which punches above its weight for a city this size. For My Tale of Two Cities, Chris Rawson and I assembled Pittsburghers working on Broadway in Times Square to sing “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” Afterwards, we spoke to Kathleen Marshall in front of the August Wilson Theater and she shared that why she thought so much talent came from Pittsburgh. While New York and LA have great teachers, their classes are hard to get into. Whereas in Pittsburgh, young people can have access to so many resources and the space and time to develop their talent.

4) A strong point of view. Let’s face it, Pittsburgh can piss you off, which is the kind of anger that drives you as an artist. It gives you something to say. That was true for Pitt alum and Pulitzer-Prize winner Michael Chabon called his first novel Mysteries of Pittsburgh and Wonder Boys where Michael Douglass played Grady Tripp was loosely inspired by English professor Chuck Kinder. Rob Marshall has talked about wanting to make his own Billy Elliot about growing up wanting to be a dancer in a steel town. Pittsburgh is hardly a perfect place, and that has led artists to create from Romare Bearden whose paintings inspired several August Wilson plays to the brilliant internationally acclaimed sculptor Vanessa German who started The Art House in Homewood to help give kids from that neighborhood a chance to create and realize their own importance.

5) Starving artists and natural selection. By not making it possible to really make a living in Pittsburgh in the “arts,” Pittsburgh often drive talent to places like New York and L.A. When we spoke to Billy Porter in front of the August Wilson Theater, (pre-him becoming a household name), he said it was nice how Pittsburgh would name him “Entertainer of the Year,” but where was the investment in his and other artist’s talent? Jeff Goldblum, whose colorful mother Shirley I got to meet on several occasions and who worked as a radio broadcaster, once told me how he still dreams about Pittsburgh. But if Jeff had stayed in the Burgh, would he have had the ubiquitous career in movies he has had? August Wilson worked as a short-order cook and a dishwasher through his twenties as he struggled to find his voice as a writer. He didn’t start writing his Pittsburgh plays until he moved to Minneapolis and it was there he started hearing the voices of people he had known in The Hill District. His first play Jitney premiered here, but August was never paid as a writer in the town he immortalized, and it was Broadway producers who bet on all the plays he set here.

The Legacy of These Mothers and Hope for Our Future

I still don’t fully understand why I myself am back in Pittsburgh, but my return was unusual enough to land me on Oprah who kept saying in disbelief: “He found happiness in Pittsburgh, even.” During the filming of My Tale of Two Cities, I took my mother back to our townhouse apartment which had been turned into a beauty salon. My mother noted how ironic it was that I had moved back to her least favorite city. As we walked through what I called the “mousehole” of Pembroke Mews to the street where Stevie Soderbergh, Tom Kurlander, Michael Alteri, and I had played football, I told her my dilemma about having left L.A. where I was paid well for writing, and though I loved teaching and making movies with my students, it was obviously far less lucrative. I asked my mother if “you’re talented, do you have to leave Pittsburgh?”

Ellen Weiss Kander, who before coming back here to raise her kids had been a successful Wall Street attorney, often joked to our board chair Anne Lewis, that though Steeltown did some good, we would have made more money opening a lemonade stand. Tragically, Ellen passed away way too young, but the work she set in motion along with Anne, Audrey, our Steeltown advisers and all their mothers, has had an impact. Pittsburgh is no longer “Hollywood’s Best Kept Secret” as film tax credits which the Steeltown advisers helped advocate for have led to over a billion dollars in films and TV productions shot in Western PA. Steeltown’s“Youth and Media” programs gave young people hands-on opportunities to learn how to make movies and TV shows including the award-winning, student-produced “The Reel Teens” which aired on the local Fox affiliate. While Steeltown closed its doors several years ago, its Steeltown Film Academy continues in a new iteration at WQED. The University of Pittsburgh where I teach now has a robust film and media and broadcast production programs as well as the state-of-the art Pitt Studios built with a partnership of NEP, which provides mobile production for events from the Super Bowl to the Olympics to the Oscars. And I am the program director of a Pitt in LA program which each year gives students exposure to leading film and television professionals including dozens of my own students who have had successful careers in the industry. (This all came about because of Pitt alum and Lionsgate executive John Dellaverson who I got to know when he returned to his native New Castle to visit his mother that became its own segment on WQED.)

Today there are scores of young people working in the film and television industry who got their start through programs at Steeltown, but sadly, too many still have to leave to making a living. And the same time, there are now are artists and filmmakers coming to Pittsburgh and finding it an increasingly attractive place to work compared to New York and LA which have become insanely expensive. And this past June, Bernie Goldmann came to speak to my students for the Pitt in LA program, and predicted with AI programs like SORA, soon any kid in a Pitt dorm room could do what he and Warner Brother spent millions doing when he made 300.

When she won her Academy Award in Fences, Viola Davis said that our best stories often lay in our graveyards and she wanted to thank August Wilson for exhuming them. August often credited his mother Daisy for his work. And now a whole new generations of young people will be inspired through programs at Daisy Wilson Arts Community at the August Wilson House.

I am nowhere near the talented writer August Wilson was, nor can I paint like Andy Warhol, or dance like Gene Kelly. But like them, I know it was my Pittsburgh upbringing, for better and worse, that shaped me. I hope by sharing the stories my mother shared with me and Pittsburgh’s other sacred stories, I can honor the people I have met on this journey and maybe even inspire a few others along the way. For there is one thing I have learned in all this— it is all about the mothers.

Watch Pittsburgh: Hollywood’s Best Kept Secret below and My Tale oF Two Cities clinking the link here.